Being and Having: Copulas & Possessives

Today I want to talk about two major ideas in Marešidi: Copulars and Possessives, statements which convey being and having. They seem like very simple ideas, but there are various different ways that languages can express them.

First, let’s discuss possessives.

In the last post, “Pronouns,” I introduced the possessive pronoun. It surfaces as a suffix on the object which is possessed, conjugated according to the possessor.

Note that, while I often put a hyphen before suffixes when transcribing, in Marešidi script the “o” joins the preceding consonant.

Marešidi is similar to Russian in that it does not have a verb meaning “to have.” Possessive relationships are proximal, meaning that “having something” is thought of as “something which is close or available to someone.” The sentence, “I have a car,” in Russian is “У меня есть машина,” but it literally translates as, “To me there is a car.” It lacks the same ideas of ownership as English’s have and it emphasizes the fact that possession can be volatile and subject to many factors.

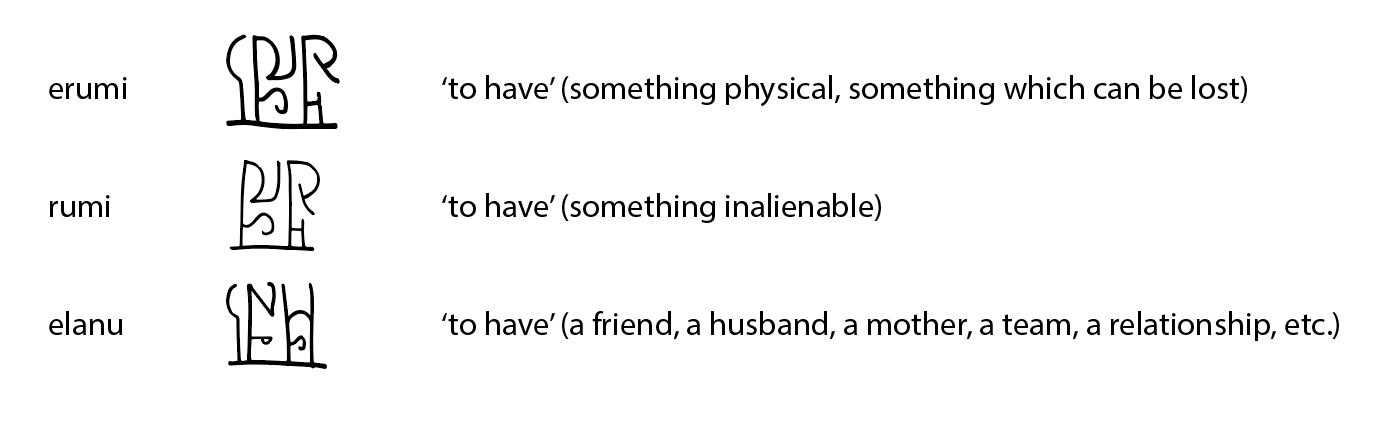

Here are the primary verbs used for possession in Marešidi:

The middle one, rumi, behaves normally in terms of the basic subject-verb-object structure of Marešidi, though it is not used with things which can be lost and will almost never refer to a physical thing. The only exception to this is the body parts (and yes, even those that can technically be ‘lost’).

But, let’s say you wanted to say our example from above, “I have a car.” Since cars as we know them don’t exist on Mars in my story, we’ll do a rough translation of “a car” as “a vehicle for movement,” rui-turuž, with rui being the article, “a.” The verb that we will use is the first in the list, erumi, but, even though the word that comes before it is still a subject, it is going to be a passive construction, similar to “a car is had by me,” or more literally, “a car is available for me.” Erumi comes from the verb rumi; the e- prefix indicates the need for the passive voice. Since “a car” is a singular, third-person subject, the conjugation suffix will be -ro.

As you can see, the first-person pronoun, demu, is at the end of the sentence. The -b suffix is a shortened form of the adposition, -ob, meaning “for.” It comes after the word it joins to, unlike in English.

Even though a possessor is usually indicated, it is often deleted because the speaker is often implied to be the possessor. If you chopped off the demu-b above, the sentence would be understood the same even though technically it translates to, “a car is available.”

Another way that erumi can be translated is as “to be an affliction (for someone/something).” Here are two examples of when it would be translated this way. In English, we use the verb to have.

The verb elanu comes from the verb lanu, meaning ‘to guard or uphold,’ and it is the possessive verb used when referring to relationships with people. Similar to erumi, it is a passive construction and the possessor can often be deleted. Elanu can also be used in place of erumi in order to express an emotional closeness to something/somewhere. Note that, the adposition which joins to the possessor is -th or -oth, depending on if it joins to a vowel or consonant respectively. It means “by” as opposed to -ob meaning “for.” Here are some examples:

Now, let’s learn about copular statements.

In Marešidi, there are verbs which are translated as “to be.” They are as follows:

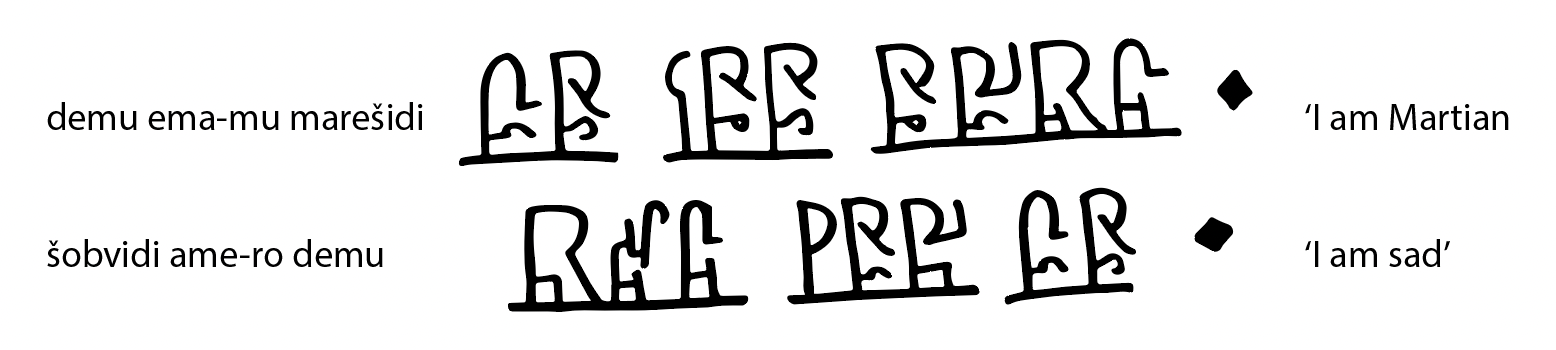

Take a look at the following copular sentences and try to look for the different structure:

You may have noticed that the pronoun demu comes before the verb in the first example and after the verb in the second. The main difference between these verbs is that ema is used for things which are intrinsic to a person/thing or something which pertains to its identity, such as one’s height, occupation, nationality, appearance, etc, while ame is used for things which are fleeting such as emotions or one’s temporary location. If you know Spanish, it is similar to the difference between ser and estar. Here are two sentences expressing location, one permanent and one temporary, see if you can determine which is which.

In the first, tho-per meaning ‘the building’ is the subject and muth-up meaning ‘to the south’ is its complement. In the second, tho-per is before the verb, though there is another suffix, -av meaning ‘in.’ Even though the subject usually comes before the verb, in this case, the complement must come before the verb. The subject of the sentence, demu meaning ‘I,’ is found after the verb, and we can see this by the matching conjugation, -mu. This word-order flip is the main difference in the usage of these verbs: when using ema, the subject comes before the verb, when using ame, the complement comes before the verb.

If we change the verbs and the order of the sentences above, we will get messages that imply something different. Muth-up ame-ro tho-per still technically means, “The building is to the south,” but it implies it won’t be there all that long. Demu ema-mu tho-per-av still means “I am in the building,” but it implies that you’ll never leave it.

Until next time!

Dillon